Visiting looking at the Mona Lisa (Credit: pixabay.com)

PARIS, France — No name is as synonymous with the Renaissance as Leonardo da Vinci. More than just a painter, architect, engineer, sculptor, and scientist, da Vinci was an absolute intellectual titan of his age, introducing concepts and ideas that were centuries ahead of their time. Besides his sheer brilliance, da Vinci is also rumored to have placed hidden meanings, puzzles, and messages into his works requiring careful examination to identify. For example, the golden ratio is present in a number of his paintings.

Now, fascinating new research from the American Chemical Society has uncovered that da Vinci was likely experimenting with the base layers underneath his paintings. Researchers found that samples taken from two of his most iconic paintings, “Mona Lisa” and the “Last Supper,” show the painter likely conducted experiments with lead(II) oxide that resulted in the formation of a rare compound called plumbonacrite below the artwork.

The man may have lived and died centuries ago, but his works still inspire awe today and carry a certain air of mystery. The “Mona Lisa” has an uncanny way of gazing back at viewers, and one can't help but wonder how da Vinci was sketching tanks and primitive flying machines back in the 15th century. Scientists and scholars alike have long scoured his writings and artworks in search of hidden clues or meanings, and many of his paintings from the early 1500s (including the “Mona Lisa”) were painted on wooden panels that required a thick, “ground layer” of paint before adding the artwork.

Researchers have discovered that while other artists of the time typically used gesso as a ground layer, da Vinci went his own way by laying down thick layers of lead white pigment and infusing his oil with lead(II) oxide, which is an orange pigment that would have conferred specific drying properties to the paint above.

da Vinci also employed a similar technique on the wall underneath his iconic “Last Supper” — which was a notable departure from the traditional, fresco technique predominantly used at the time. So, in an effort to further investigate these unique layers, Victor Gonzalez of Université Paris-Saclay, ENS Paris-Saclay, and colleagues set out to apply updated, high-resolution analytical techniques to small samples from da Vinci's two iconic paintings.

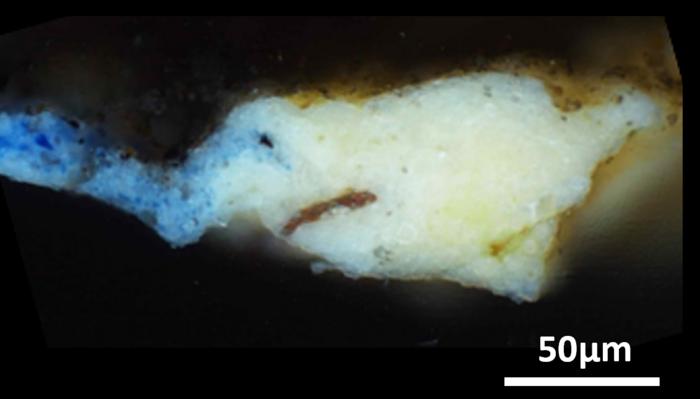

The research team ultimately carried out their analyses on a tiny, “microsample” that had been previously taken from a hidden corner of the “Mona Lisa,” in addition to 17 microsamples obtained from the surface of the “Last Supper.” Then, via X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy techniques, study authors determined that the ground layers of the artworks not only contained oil and lead white, but a much rarer compound as well: plumbonacrite (Pb5(CO3)O(OH)2).

This material has never been seen in Italian Renaissance paintings before, but it has been detected in later paintings by Rembrandt created in the 1600s. Plumbonacrite is only stable under alkaline conditions, indicating its formation stemmed from a reaction between the oil and lead(II) oxide (PbO). Notably, still intact grains of PbO were also seen in most of the samples analyzed from the “Last Supper.”

While painters and artists have been known to add lead oxides to pigments to encourage drying, this technique has not been proved experimentally for paintings from the Italian Renaissance. Moreover, when study authors searched through da Vinci's writings, the only evidence they found of PbO was in reference to skin and hair remedies - despite it being known as quite toxic nowadays! Still, these findings at the very least suggest lead oxides had a place on the old master’s palette, and may have helped create some of the greatest masterpieces we know today.

The study is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

You might also be interested in:

- Leonardo da Vinci may have discovered the secrets of gravity centuries before physicists did

- 10 Everyday Sources Of Lead Poisoning Still Causing Public Health Concerns

- Mona Lisa's hands hint at new treatment for high cholesterol

- Best Places To Visit In Italy: Top 5 Must-See Cities, According To Travel Experts

The EPA would shut him down today

I studied art in the 1990s thru about 2004. We routinely used gesso as the base for oil paintings but learned that lead white while toxic was better. I even bought a tub of lead white but never used it in a painting. So I'll say that while we didn't know Da Vinci in particular had used it, it was common knowledge that it was used by great masters down thru history.