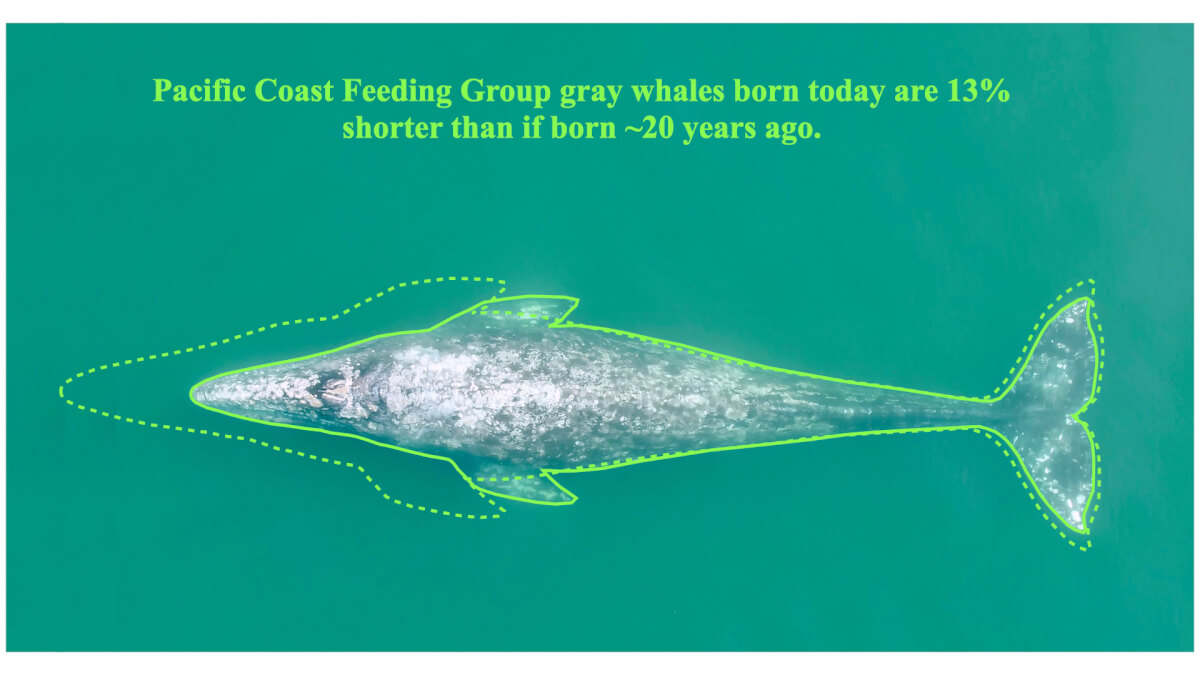

Two PCFG gray whales. (Credit: Oregon State University)

NEWPORT, Ore. — Whales are still larger-than-life creatures, but a concerning new study finds they're a lot smaller today than they used to be. Scientists from Oregon State University have discovered a significant decrease in the body length of gray whales in the northeastern Pacific, signaling a troubling response to shifting conditions in Earth's oceans.

The detailed research, published in Global Change Biology, reveals that whales in this region have shrunk by more than 13% over the last 20 years. On average, that means gray whales are roughly five feet and five inches shorter than they were at the start of the 21st century. Study authors fear this could be the first sign of this species' eventual extinction.

“This could be an early warning sign that the abundance of this population is starting to decline, or is not healthy,” says K.C. Bierlich, co-author of the study and an assistant professor at OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute, in a media release. “And whales are considered ecosystem sentinels, so if the whale population isn’t doing well, that might say a lot about the environment itself.”

How Did Scientists Discover This?

At the heart of this research lies a sophisticated use of drone-captured aerial imagery, allowing for unprecedented precision in measuring whale growth patterns. Researchers developed a “Bayesian hierarchical model” to estimate the individual growth trends of gray whales over time. This method involves layering observations of whale sizes derived from high-resolution images and coupling them with extensive environmental data.

Specifically, the study authors looked at the Pacific Coast Feeding Group (PCFG), a small group of roughly 200 gray whales. These whales are part of the larger Eastern North Pacific (ENP) population, which includes approximately 14,500 whales.

The gray whales in the study usually stay closer to the shore along the Oregon coast and feed in shallower, warmer waters than whales in the Arctic.

Key Findings

Gray whales, particularly females, have shown a notable reduction in maximum body length since the year 2000. This decline is strongly tied to changes in oceanic conditions, evidenced by two key oceanographic metrics — the Pacific Decadal Oscillation index and a measure of upwelling intensity relative to relaxation events.

“Without a balance between upwelling and relaxation, the ecosystem may not be able to produce enough prey to support the large size of these gray whales,” explains co-author Leigh Torres, an associate professor and director of the GEMM Lab at OSU.

These metrics serve as proxies for habitat quality, suggesting that deteriorating ocean conditions, potentially driven by climate change, are influencing whale growth and potentially their survival and reproductive capabilities.

“We haven’t looked specifically at how climate change is affecting these patterns, but in general we know that climate change is affecting the oceanography of the Northeast Pacific through changes in wind patterns and water temperature,” says Enrico Pirotta, lead author of the study and a researcher at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “And these factors and others affect the dynamics of upwelling and relaxation in the area.”

Study Limitations

The precision of drone measurements, while advanced, still introduces some degree of uncertainty due to varying conditions under which data were collected. Furthermore, the environmental metrics used, though indicative, do not capture the full complexity of the factors that may influence whale growth, such as prey availability and other ecological pressures.

What Does This Mean for the Future of Whales?

The implications of these findings resonate with conservation efforts and global policymaking. The decline in whale size not only affects their health and ecological role but may also reflect broader environmental shifts that could have a severe trickle-down effect throughout the ocean food chain.

“Our results contribute to the mounting evidence that the body size of some populations of large marine predators is shrinking,” the researchers write in their report. “The body size of predators can have cascading consequences on their prey.”