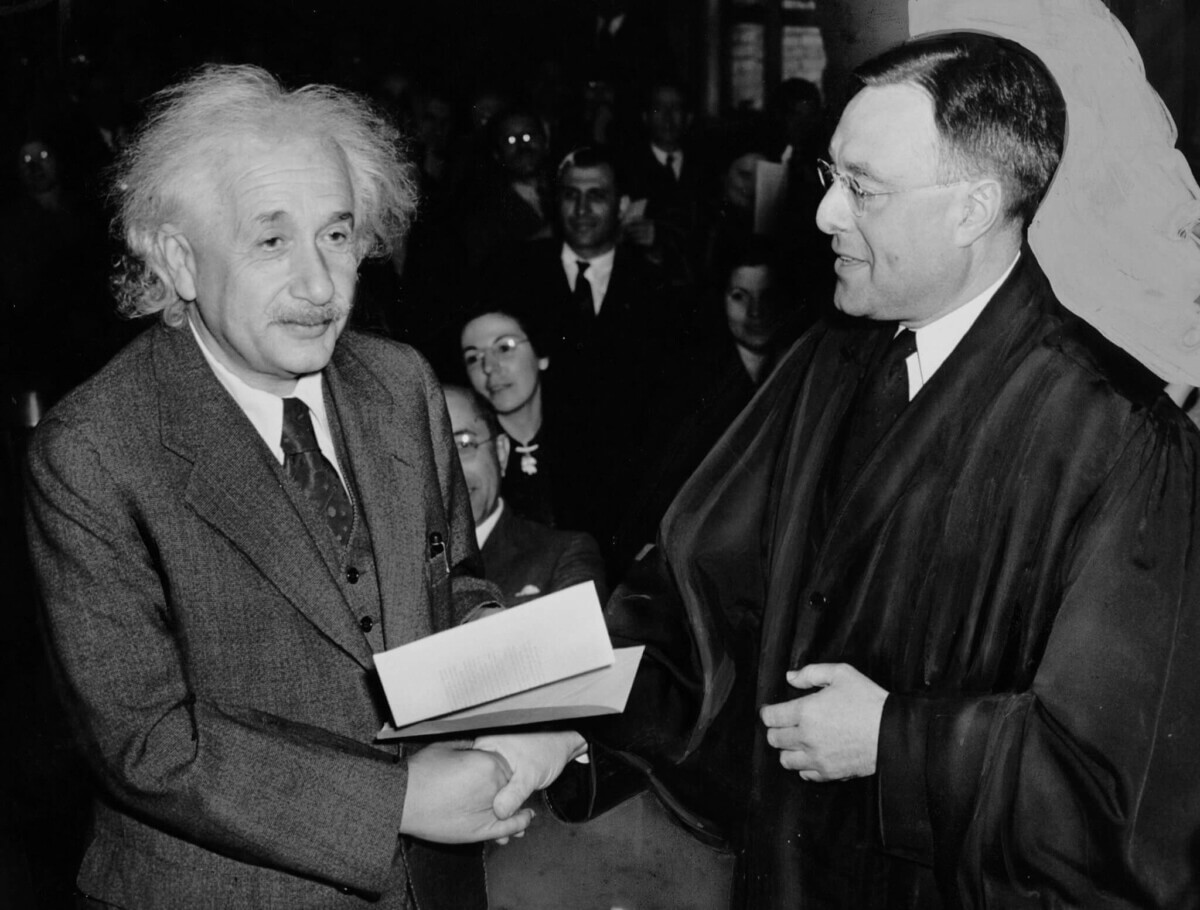

WikiImages / pixabay.com

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Millions of young scientists daydream of one day becoming the next Albert Einstein, but a new study says they should probably look up to a Nikola Tesla or Thomas Edison instead. Researchers from Penn State University say that young people are better motivated in scientific fields when they look up to success stories forged through hard work as opposed to genetically-gifted genius.

“There's a misleading message out there that says you have to be a genius in order to be a scientist,” comments study author Danfei Hu, a doctoral student at Penn State, in a release. “This just isn't true and may be a big factor in deterring people from pursuing science and missing out on a great career. Struggling is a normal part of doing science and exceptional talent is not the sole prerequisite for succeeding in science. It's important we help spread this message in science education.”

Today, an alarming number of students who set out for a career in science end up giving up on their ambitions. This is referred to as the “leaking STEM pipeline.” Researchers theorize this is at least partially due to the societal belief that one must be a genius in order to really make a scientific impact.

So, in an effort to solve this problem, the research team at Penn State set out to examine the influence of role models on young scientists. More specifically, they wanted to investigate how aspiring scientists' own beliefs on a role model effects their motivation patterns.

“The attributions people make of others' success are important because those views could significantly impact whether they believe they, too, can succeed,” comments co-author Janet N. Ahn, an assistant professor of psychology at William Paterson University. “We were curious about whether aspiring scientists' beliefs about what contributed to the success of established scientists would influence their own motivation.”

In all, three experiments were conducted with this in mind. The first involved 176 people, the second included 162, and the third featured 288 participants.

The first study asked participants to read a story about some struggles a scientist experienced during his career. However, while all participants read the same story, half were told it was about Einstein, while the others were told it was about Edison. Surprisingly, even though they had all read the exact same story, those who believed the tale was about Einstein were more likely to believe “natural brilliance” was the reason for Einstein's success, while the other half attributed Edison's success to hard work. Those in the Edison group were also more motivated to solve a few complex math equations.

“This confirmed that people generally seem to view Einstein as a genius, with his success commonly linked to extraordinary talent,” Hu says. “Edison, on the other hand, is known for failing more than 1,000 times when trying to create the light bulb, and his success is usually linked to his persistence and diligence.”

The second experiment was very similar to the first, but participants were told the story was either about Einstein or a completely fictional scientist named Mark Johnson. Those who read about this Johnson character were much more likely to believe that success can be attained without natural genius, and were more likely to perform well on a math exam.

Finally, for the third experiment, the research team wanted to see if young aspiring scientists felt inadequate in comparison to legendary figures like Einstein and Edison. So, this time around, they randomly assigned participants to read a story supposedly about either Einstein, Edison, or an anonymous scientist.

In comparison to the unknown figure, Edison motivated participants while Einstein actually seemed to demotivate them.

“The combined results suggest that when you assume that someone's success is linked to effort, that is more motivating than hearing about a genius's predestined success story,” Hu says. “Knowing that something great can be achieved through hard work and effort, that message is much more inspiring.”

The study's authors believe their findings can help shape science education practices across a variety of age groups.

“This information can help shape the language we use in textbooks and lesson plans and the public discourse regarding what it takes to succeed in science,” Hu concludes. “Young people are always trying to find inspiration from and mimic the people around them. If we can send the message that struggling for success is normal, that could be incredibly beneficial.”

The study is published in Basic and Applied Social Psychology.