Artist’s impression of a gliding reptile Kuehneosaurus. (CREDIT: Mike Cawthorne)

BRISTOL, United Kingdom — It's not everyday a college student comes across a 200 million-year-old flying reptile, but that's exactly what happened in the United Kingdom. Researchers at the University of Bristol made the astonishing discovery in the Mendip Hills of Somerset, revealing that ancient, winged reptiles, known as Kuehneosaurs, once inhabited this area. These findings offer new insights into the diverse wildlife that thrived millions of years ago.

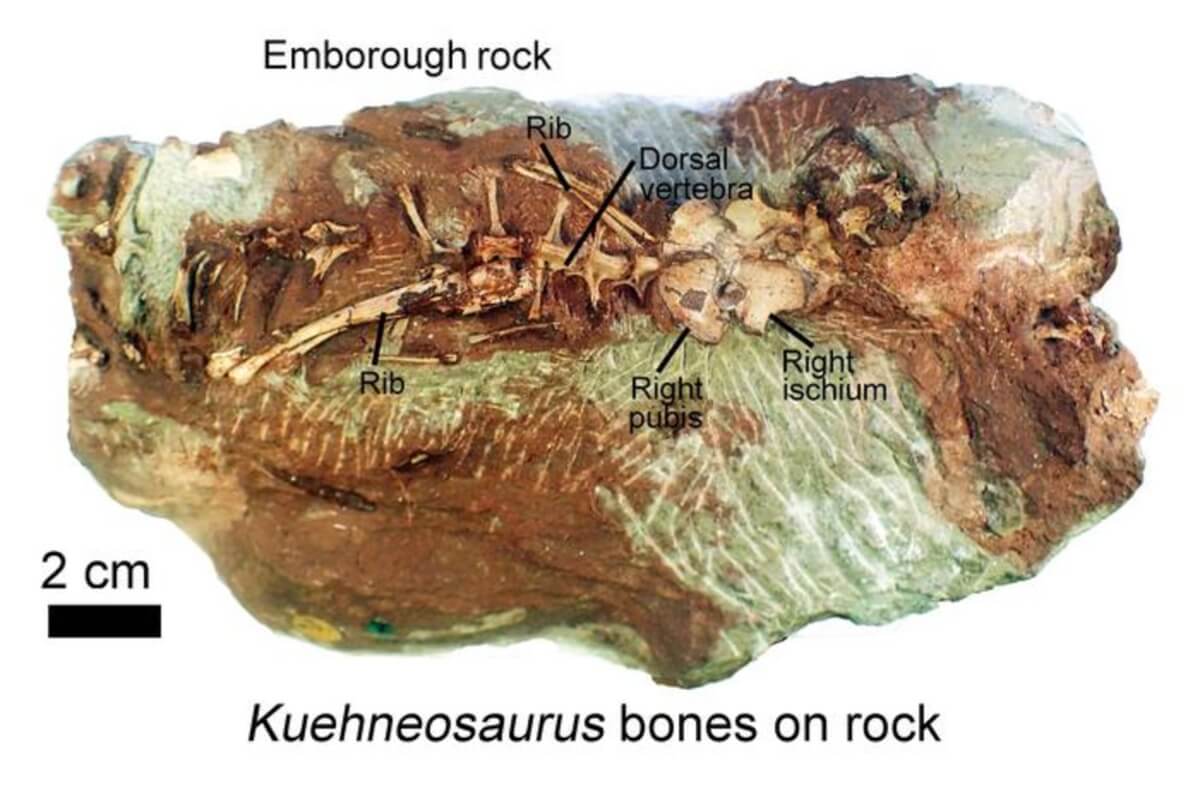

Kuehneosaurs, resembling lizards in appearance, were actually more closely related to the ancestors of modern-day crocodilians and dinosaurs. These small creatures, which could comfortably sit in the palm of a hand, existed in two distinct species. One had expansive wings, while the other sported shorter wings, both utilizing a layer of skin stretched over extended side ribs. This unique adaptation allowed them to glide effortlessly from tree to tree, similar to the modern flying lizard Draco found in southeast Asia.

The discovery was made by University of Bristol masters student Mike Cawthorne, who was examining numerous reptile fossils from limestone quarries in the area. These quarries once formed part of a large sub-tropical island during the Late Triassic period, known as the Mendip Palaeo-island.

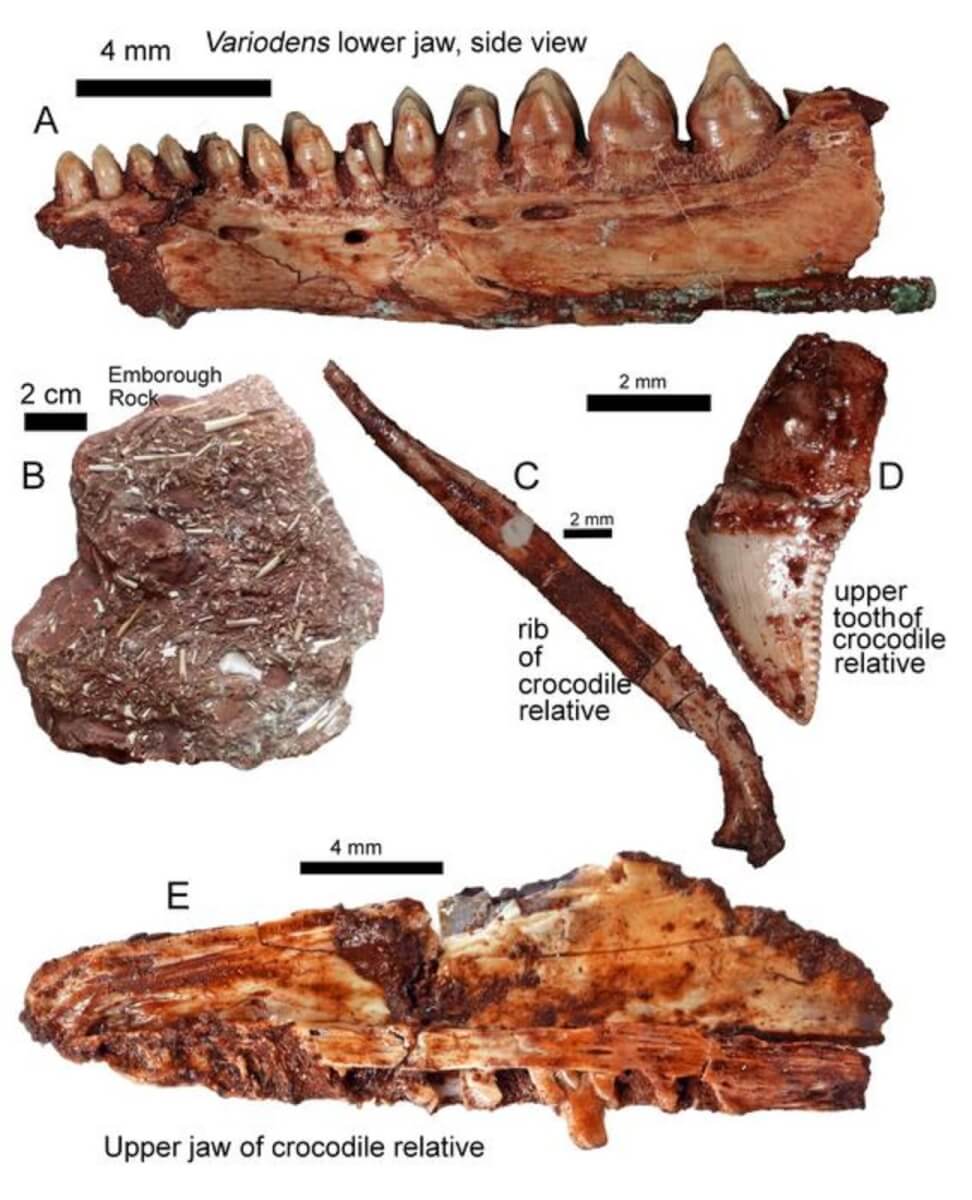

The study not only highlights the Kuehneosaurs but also notes the presence of other reptiles with intricate dental structures. These include the trilophosaur Variodens and the aquatic Pachystropheus, the latter likely resembling a modern otter in behavior, possibly feeding on shrimps and small fish.

“All the beasts were small,” says Cawthorne in a university release. “I had hoped to find some dinosaur bones, or even their isolated teeth, but in fact I found everything else but dinosaurs.”

“The collections I studied had been made in the 1940s and 1950s when the quarries were still active, and paleontologists were able to visit and see fresh rock faces and speak to the quarrymen,” Cawthorne continues.

Mike Benton, professor at the University Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, explained the challenges in identifying the fossil bones, which were mostly found separated and not as part of a complete skeleton.

“However, we have a lot of comparative material, and Mike Cawthorne was able to compare the isolated jaws and other bones with more complete specimens from the other sites around Bristol,” notes Benton.

The study suggests that the Mendip Palaeo island, stretching nearly 30 kilometers long, was a hub for diverse small reptiles that fed on the abundant plants and insects of the time. While no dinosaur bones were found in this particular study, their presence in the area is likely, as dinosaur remains have been discovered in other locations of the same geological age around Bristol.

The Mendip Hills area, around 200 million years ago, was part of an archipelago set in a warm sub-tropical sea.

“The bones were collected by some great fossil finders in the 1940s and 1950s including Tom Fry, an amateur collector working for Bristol University and who generally cycled to the quarries and returned laden with heavy bags of rocks,” explains Dr. David Whiteside, of the University of Bristol.

“The other collectors were the gifted researchers Walter Kühne, a German who was imprisoned in Great Britain in the second world war, and Pamela L. Robinson from University College London. They gave their specimens to the Natural History Museum in London and the Geological collections of the University of Bristol.”

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the Geologists Association.