(Photo by airdone on Shutterstock)

NOTTINGHAM, England — Are you an open book, your face broadcasting every passing emotion, or more of a stoic poker face? Scientists at Nottingham Trent University say that wearing your heart on your sleeve (or rather, your face) could actually give you a significant social advantage. Their research shows that people who are more facially expressive are more well-liked by others, considered more agreeable and extraverted, and even fare better in negotiations if they have an amenable personality.

The study, led by Eithne Kavanagh, a research fellow at NTU’s School of Social Sciences, is the first large-scale systematic exploration of individual differences in facial expressivity in real-world social interactions. Across two studies involving over 1,300 participants, Kavanagh and her team found striking variations in how much people moved their faces during conversations. Importantly, this expressivity emerged as a stable individual trait. People displayed similar levels of facial expressiveness across different contexts, with different social partners, and even over time periods up to four months.

Connecting facial expressions with social success

So what drives these differences in facial communication styles and why do they matter? The researchers say that facial expressivity is linked to personality, with more agreeable, extraverted and neurotic individuals displaying more animated faces. But facial expressiveness also translated into concrete social benefits above and beyond the effects of personality.

In a negotiation task, more expressive individuals were more likely to secure a larger slice of a reward, but only if they were also agreeable. The researchers suggest that for agreeable folks, dynamic facial expressions may serve as a tool for building rapport and smoothing over conflicts.

Across the board, the results point to facial expressivity serving an “affiliative function,” or a social glue that fosters liking, cooperation and smoother interactions. Third-party observers and actual conversation partners consistently rated more expressive people as more likable.

Expressivity was also linked to being seen as more “readable,” suggesting that an animated face makes one's intentions and mental states easier for others to decipher. Beyond frequency of facial movements, people who deployed facial expressions more strategically to suit social goals, such as looking friendly in a greeting, were also more well-liked.

“This is the first large scale study to examine facial expression in real-world interactions,” Kavanagh says in a media release. “Our evidence shows that facial expressivity is related to positive social outcomes. It suggests that more expressive people are more successful at attracting social partners and in building relationships. It also could be important in conflict resolution.”

Taking our faces at face value

The study, published in Scientific Reports, represents a major step forward in understanding the dynamics and social significance of facial expressions in everyday life. Moving beyond the traditional focus on static, stylized emotional expressions, it highlights facial expressivity as a consequential and stable individual difference.

The findings challenge the “poker face” intuition that a still, stoic demeanor is always most advantageous. Instead, they suggest that for most people, allowing one's face to mirror inner states and intentions can invite warmer reactions and reap social rewards. The authors propose that human facial expressions evolved largely for affiliative functions, greasing the wheels of social cohesion and cooperation.

The results also underscore the importance of studying facial behavior situated in real-world interactions to unveil its true colors and consequences. Emergent technologies like automated facial coding now make it feasible to track the face's mercurial movements in the wild, opening up new horizons for unpacking how this ancient communication channel shapes human social life.

Far from mere emotional readouts, our facial expressions appear to be powerful tools in the quest for interpersonal connection and social success. As the researchers conclude, “Being facially expressive is socially advantageous.” So the next time you catch yourself furrowing your brow or flashing a smile, know that your face just might be working overtime on your behalf to help you get ahead.

Paper Summary

Methodology

To quantify facial expressivity, Kavanagh and colleagues employed a cutting-edge approach blending real-world social interactions with high-tech expression tracking. In the first study, 52 participants engaged in semi-structured video calls with a conversation partner (actually a study confederate to keep interactions consistent). The multi-part calls guided participants through a range of typical social contexts, from getting acquainted to negotiating over dividing a monetary bonus.

Throughout these interactions, the researchers used iMotions software to track 16 distinct facial movements, such as brow furrowing and lip curling, based on the gold-standard Facial Action Coding System. From these building blocks, they computed six core metrics of facial expressivity, capturing the frequency, duration and diversity of participants' facial expressions. Participants also completed personality surveys and were rated on likeability by their conversation partner and outside observers.

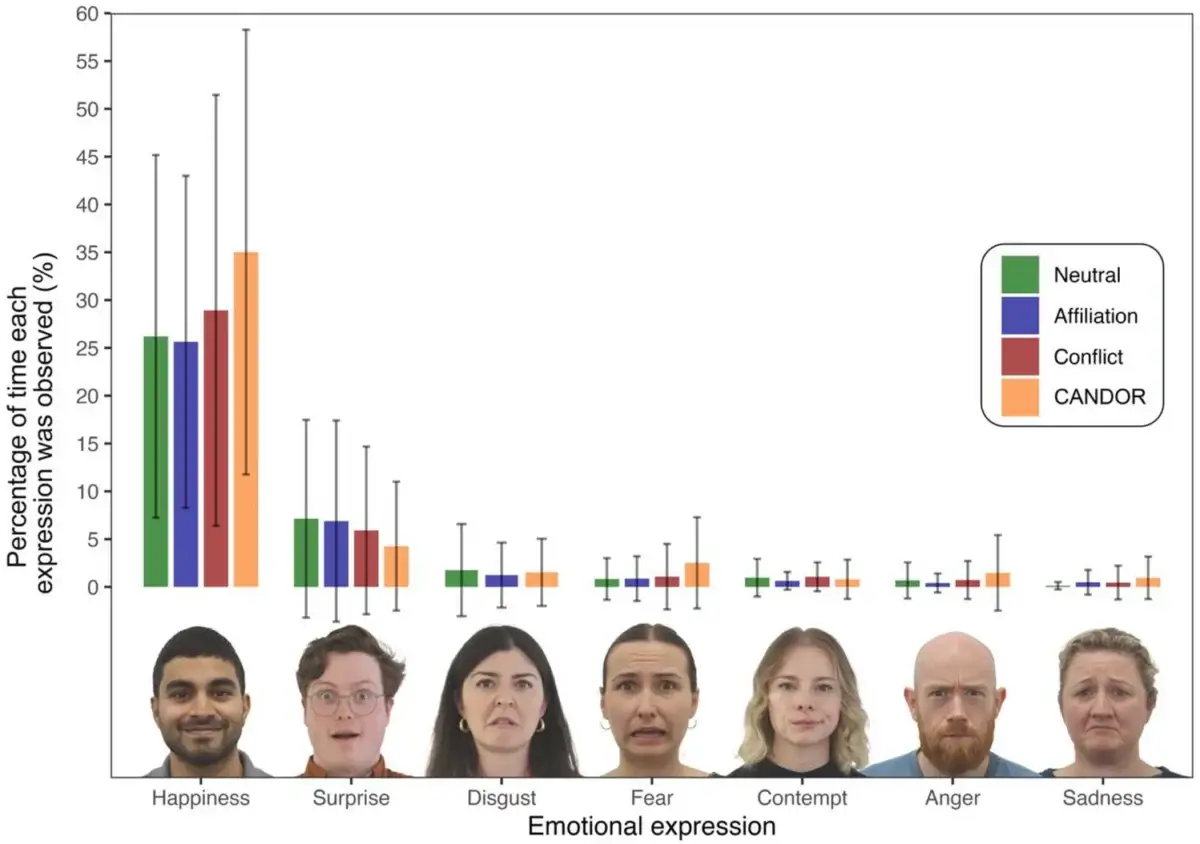

In the second study, the researchers validated these findings in a larger existing dataset, the CANDOR corpus, comprising recordings of 1,315 participants in unstructured 30-minute video conversations. Again, iMotions was used to track facial expressivity in the first five minutes of each chat.

Results

Crunching the numbers, distinct “facially expressive” and “facially reserved” styles emerged that remained remarkably consistent across contexts and time. In both studies, participants' facial animation while getting acquainted predicted how expressive they would be in more emotionally charged situations like negotiations. In the larger dataset, expressiveness with one conversation partner strongly correlated with expressiveness with others, and even at a 4-month follow-up.

These individual differences in facial expressivity, in turn, translated into clear interpersonal advantages. Across both studies, the chattier the face, the more well-liked the person. In the second study, a one-point boost in facial expressivity corresponded to a 16% jump in partner-rated likeability. Expressiveness also tracked with seeming more readable and deploying facial expressions more skillfully to convey social messages.

The personality signature of facial expressivity also replicated across studies. More agreeable people consistently displayed more mobile faces. In study 2, extraverted and neurotic individuals were also more expressive. However, the social benefits of facial expressivity could not simply be reduced to a “halo effect” of having a more desirable personality. Controlling for agreeableness, extraversion and neuroticism, expressiveness still predicted likeability in its own right.

Limitations

While offering unprecedented insights into real-world facial communication, the study has some limitations. The vast majority of participants were North American or European, raising questions about the universality of the findings. The researchers caution that cultural “display rules” - social norms guiding emotional expression - may shape how facial expressiveness is perceived and valued in different contexts.

The correlational nature of the data also makes it difficult to definitively untangle the causal links between facial expressivity, personality and social outcomes. Did agreeable negotiators secure more rewards because they were more expressive, or did getting their way make them more inclined to smile? While the findings suggest that expressivity leads to likeability, experimental designs manipulating interaction partners' facial behavior could more firmly establish cause and effect.