(Photo by Leon Overweel on Unsplash)

GAITHERSBURG, Md. — Mercury has been a public health concern for years, and scientists have kept a close eye on its presence in our oceans, food, and drinking water. Unfortunately, new research shows that one specific population is being affected by this toxic element — dolphins. Researchers have found elevated mercury levels in dolphins across the Southeastern United States, namely along the Florida and Georgia coasts.

Dolphins are considered a “sentinel species,” which means they can provide early warnings of existing or emerging health hazards to humans from the ocean. Dolphins are also larger animals that live longer, are higher up on the food chain, and share certain traits with humans. Their diet consists of a variety of small fish like croaker and spot, shrimp, and squid. All of these species are vulnerable to mercury contamination and are consumed by people as well.

“As a sentinel species, the bottlenose dolphin data presented here can direct future studies to evaluate mercury exposure to human residents,” the study authors write in a media release. Their findings are published in the journal Toxics.

The study couldn't draw conclusions about the mercury levels of Florida and Georgia residents. However, the authors did cite other research from a different group that exposed a connection between high mercury levels in dolphins in Florida's Indian River Lagoon and contamination among people living in that area. Fish are part of a healthy diet, so depending on mercury accumulation in the fish being consumed, it makes sense that locals eating them or drinking local water could experience higher levels of mercury poisoning.

At the same time, many mercury concerns have been overblown without considering all aspects of the problem. Mercury accumulation has a relation to the size of the animal. How much is absorbed by the body has a correlation with selenium content within the animal. Eating sharks, dolphins, and whales is riskier than consuming salmon or sardines.

These more common seafood choices typically have significantly less mercury in them than larger animals and also have more selenium to absorb those toxins. Selenium is a mineral that is critical for thyroid health and for blocking the absorption of mercury from seafood. Although exact selenium and mercury content will vary from fish to fish, generally speaking, most seafood that's commonly eaten will have enough selenium to cover mercury risks.

We also need to remember that mercury is naturally occurring and, therefore, cannot be 100% removed from various sources. The issue lies in the unnatural ways mercury enters our food and water supply, such as through the burning of fossil fuels, mining, and chemical manufacturing.

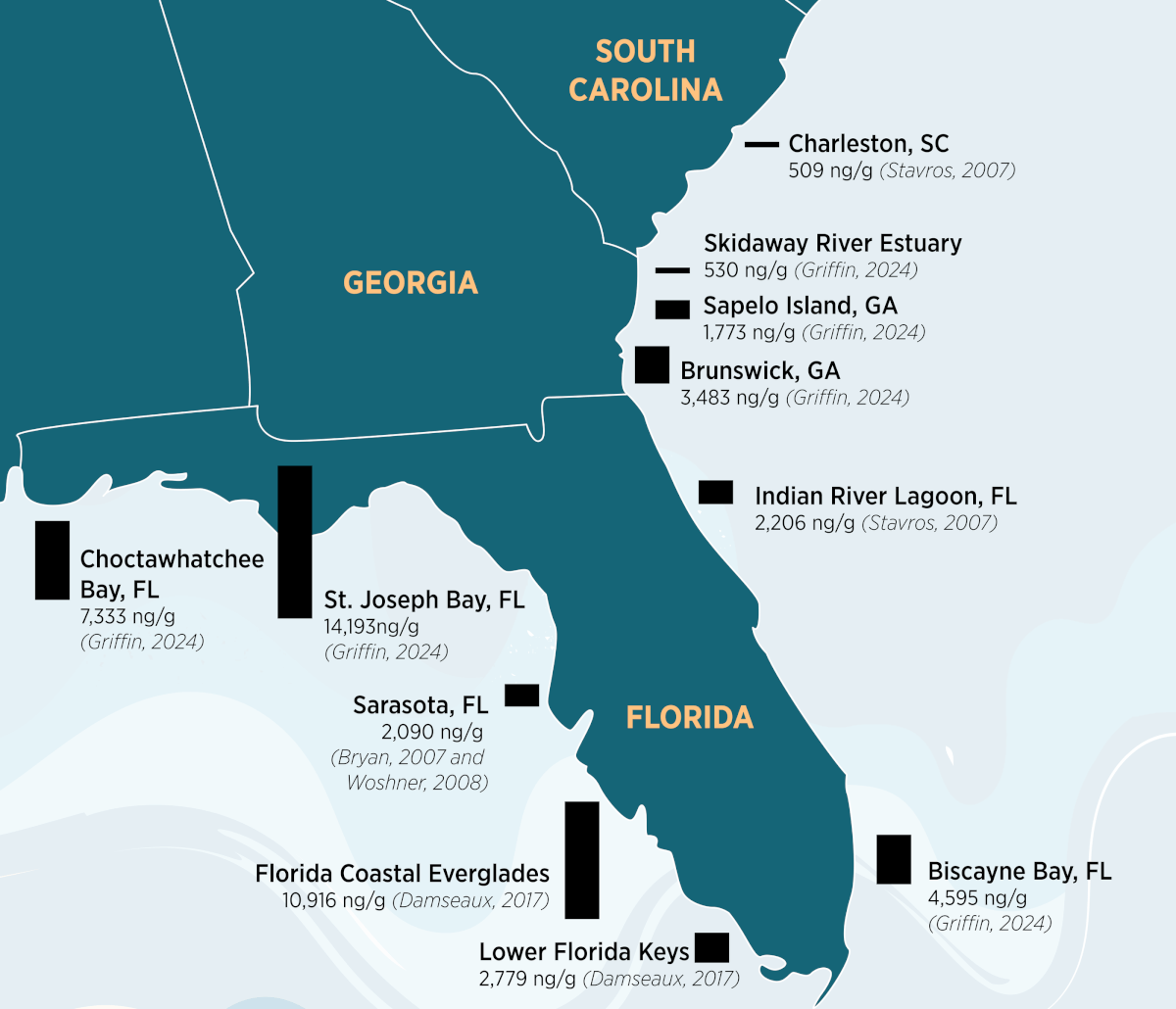

Bacteria in the water convert mercury into methylmercury, which is then absorbed or eaten by small fish. It then gets passed up the food chain to species that consume these fish, such as dolphins. For this study, the team looked at 175 skin samples collected from common bottlenose dolphins in estuaries between 2005 and 2019 from St. Joseph, Choctawhatchee, and Biscayne Bays in Florida and the Skidaway and Turtle/Brunswick River estuaries and Sapelo Island in Georgia. The measured mercury in dolphin skin is directly linked to the methylmercury in their other tissues and organs.

“NIST has been involved with dolphin health assessment and biopsy studies since 2002,” says Colleen Bryan, a research biologist and a co-author of the study from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), in a media release. “We’ve helped standardized testing protocols and collection and storage methods, so any measurements taken are highly accurate and comparable across studies.”

Results showed that mercury levels in St. Joseph Bay, where dolphins averaged 14,193 nanograms of mercury per gram (ng/g) in skin, were the highest recorded. Mackenzie Griffin, the study's lead author and a biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), says industrial activities could be partially responsible for the levels in the bay. Griffin also mentioned that the bay isn't flushed out with fresh water from other waterways, which would help lower mercury levels. For example, the authors cite previously published studies showing that dolphins near Charleston, South Carolina had the lowest average levels of mercury contamination compared to those in the Florida Coastal Everglades, which had the highest.

According to Bryan, Charleston Harbor gets mercury flushed away when the tide goes out.

“Our research adds to other studies that have consistently shown elevated levels of mercury in dolphins in the Southeast,” Bryan adds. “We hope it will lead to a better understanding of what’s happening in our oceans.”

While this research isn't conclusive when it comes to human health implications, it can help give us better directions for future studies. So far, we know that mercury in excess can have detrimental effects on the body, especially the brain. If you're concerned about mercury exposure, eating smaller fish that don't accumulate much mercury, like sardines and herring, is the way to go. Salmon is also a fine option. Eating fish multiple times per week is okay for most people, especially when we consider selenium-mercury interactions. There is much greater concern when it comes to eating significantly larger fish that feed on a wide variety of smaller fish and live for much longer periods of time.