(© pathdoc - stock.adobe.com)

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah — Many people have made decisions that they regret or that now appear irrational with the benefit of hindsight. Now, a new study on mice has found that some decisions, to a certain extent, may be beyond a person's control. The mice appeared “hard-wired” to make these decisions. Study authors from University of Utah Health say these findings may hold implications for people.

“This research is telling us that animals are constrained in the decisions they make,” says Christopher Gregg, PhD, a neurobiologist at University of Utah Health and senior author of the study. “Their genetics push them down one path or another.”

Researchers began investigating decision-making after noticing that mice would repeatedly make what appeared to be the same irrational decision. After finding a hidden stash of food (seeds), rather than staying and eating, the rodents kept returning to another location that contained food a day earlier. On this day, however, the original location was empty.

“It was as if the mice were second-guessing whether the first location really had no food,” Gregg explains in a university release. “Like they thought they had missed something.”

To Gregg and the rest of the team, this behavior just didn’t make any sense. The mice ate less because of the time they wasted continuously returning to the empty food patch. If that kind of behavior causes mice to eat less in the wild, it can be a real problem, Gregg explains, as consuming insufficient calories can be detrimental to a mouse.

Do we have genes which lead to second-guessing?

Researchers say they were surprised to discover that mice lacking a specific gene didn’t “second-guess” where to go and were thus more likely to stay and eat the food they found. Consequently, those mice consumed more calories. This was the first noted evidence suggesting genes could bias decision-making, even decisions that do not appear logical, at least to a human. In this particular case, the gene (Arc) appears quite important when it comes to compelling mice to continue searching for food even when it isn't necessary.

“We all have a clear sense of what it is like to second-guess something, but who would have thought that this type of behavior could be so profoundly affected by one gene?” comments study co-author Cornelia Stacher- Hörndli, PhD, neurobiologist. “This raises the question, are other cognitive biases under genetic control?”

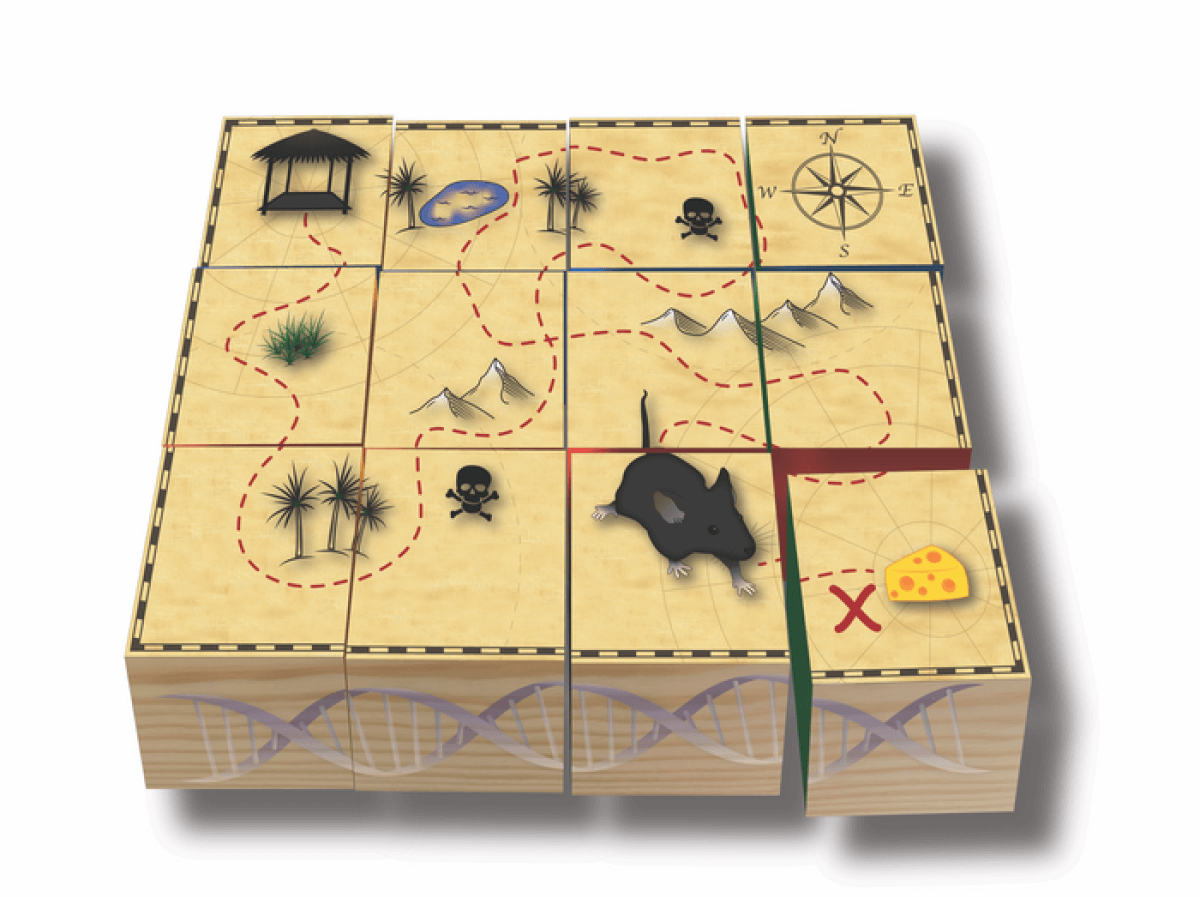

To humans, a mouse’s life usually appears very simple. When researchers placed the rodents in a naturalistic setting in Gregg’s lab, they left home, explored their surroundings, searched for food, ate some of that food, and made stops back home in between. Fairly straightforward, right? The view became more complex after a machine learning algorithm deconstructed their journeys.

A custom program put together by Gregg and study co-author Jared Emery analyzed a total of 1,609 foraging excursions, observing that the mice repeated 24 specific behavior sequences over and over. As they foraged, the mice strung these sequences together like building blocks, interspersing them with spontaneous behaviors to construct more complex behavior patterns. One such behavior was second-guessing.

“To a certain extent, you could predict the future,” Gregg remarks.

That future, however, changed for mice missing the gene (Arc). In all, six of the 24 behavior sequences were altered, and together, those differences appeared to short-circuit the second-guessing behavior. Prior research already revealed Arc plays a role in learning and memory. Generally speaking, however, this analysis showed that the mice’s memory, as well as other behaviors, remained largely intact. The implication being that the effect on those six behaviors was specific.

“One intriguing idea is that the animals evolved to make those decisions because they were somehow advantageous in the wild,” Gregg says.

One possibility is that when mice go back and forth to evaluate previous food locations, it may help them create a mental map. That map might help them find food faster the next time around.

“Genetically controlled cognitive bias may allow for effective decision-making during foraging,” the study author adds.

Of course, the big question still remains: is there a biological basis for other types of cognitive bias? Additionally, could genes really guide decision-making in human beings? More research is the only way to uncover further answers.

“I believe that this research is foundational for a new field that we are calling ‘decision genetics,’” Stacher-Hörndli concludes.

The study is published in iScience.