Fruit flies may hold the key to new helping researchers create new antibiotics.

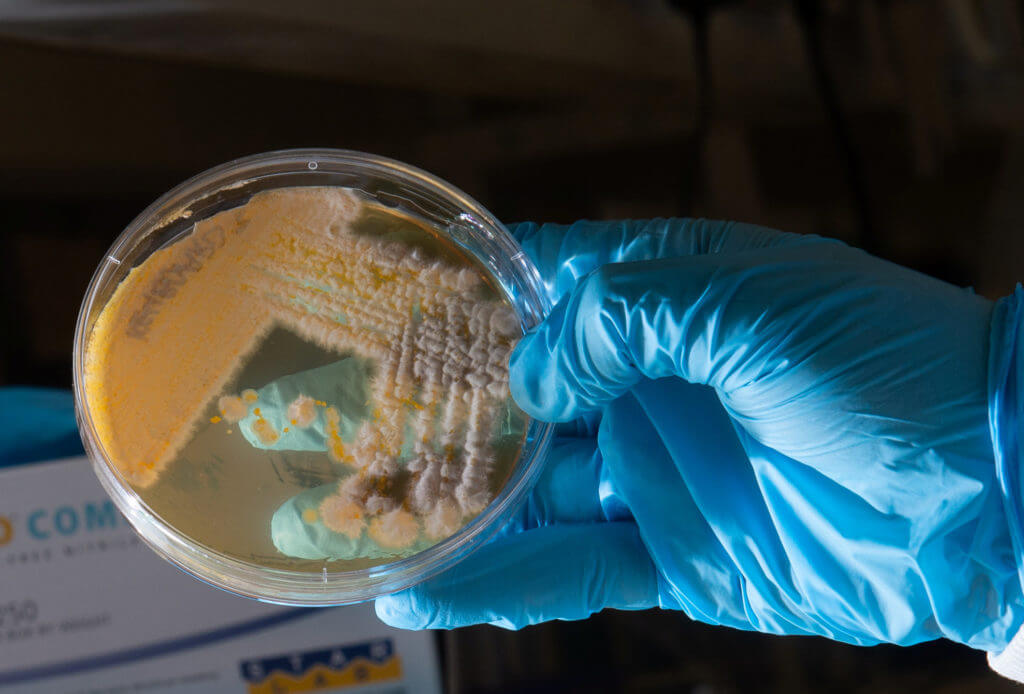

EXETER, United Kingdom — When Alexander Fleming discovered Penicillin in a moldy petri dish close to 100 years ago, it sparked the “age of antibiotics” and revolutionized medicine in the 20th century. Fast forward to today, and antibiotics have saved countless lives and are still used to treat and prevent bacterial infections. New research out of the United Kingdom, however, suggests that in certain situations the use of antibiotics can backfire and actually extend the life of some germs.

Scientists at the University of Exeter report that some antibiotics inflict a curious effect on certain bacteria — the drugs actually boost the bacteria, helping them live longer.

On a related antibacterial note, the rise of antibiotic resistance in recent years has rendered many antibiotics ineffective against certain infections. Researchers note that this is a major global issue that must be addressed. Untreatable infections could be the biggest global cause of death by 2050.

Now, this new work details for the first time that antibiotics can also help bacteria, protecting the pathogens from death. Thanks to research funded by The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, scientists uncovered that some antibiotics help relieve stress and help stop the decline of bacterial populations when they are dying out. In other words, more bacteria survive for longer periods in comparison to populations with no exposure to the antibiotic.

“The study began when we realized that surprisingly, some bacterial strains didn’t grow in the lab until we treated them with antibiotics. As a result, this is the first evidence that antibiotics can promote bacterial survival. To tackle antibiotic resistance worldwide, we need to understand far more about the impact of these drugs on the balance of bacterial ecosystems, like those in the gut microflora, or in rivers that are exposed to antibiotics. Our research is evidence of unseen side effects – we just don’t know how drugs are changing the balance of bacterial populations in those contexts,” says Professor Robert Beardmore in a university release.

In real-world environments, bacteria usually undergo periods of rapid growth, separated by periods in which growth stops due to nutrient scarcity, eventually causing the bacteria to die off. Thus far, it's been unclear how antibiotics mediate populations during those time periods.

So, researchers examined E.coli in a series of lab experiments. This approach led to the discovery that antibiotics targeting ribosomes, or factories that help cells produce protein from DNA, slowed bacteria down while they were growing yet also stopped them from dying, meaning the bacteria ended up staying alive longer.

“Many antibiotics slow the growth of bacteria, but we show that can help bacteria overcome stresses caused by a lack of nutrients that might otherwise kill them off, ultimately helping them to survive. In our experiments, this comes about because the antibiotics are antioxidants, meaning they help cells deal with some of the waste products they make as they grow,” Dr. Emily Wood concludes.

“Importantly, the antibiotic-resistant bacteria we tested didn’t get the same benefits so in our study, treatment does not promote resistance, which is unusual. Our next step will be to measure how these findings alter the dynamics of multi-species bacterial communities.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.