A mummified adult man of the Ansilta culture, from the Andes of San Juan, Argentina, dating back approximately 2,000 years. (CREDIT: Universidad Nacional de San Juan)

READING, United Kingdom — Scientists are thanking the “cement” coming from head lice for preserving DNA samples from 2,000 years ago. An international team says this substance encased ancient hairs from pre-Columbian mummies, preserving their DNA like a bug trapped in amber.

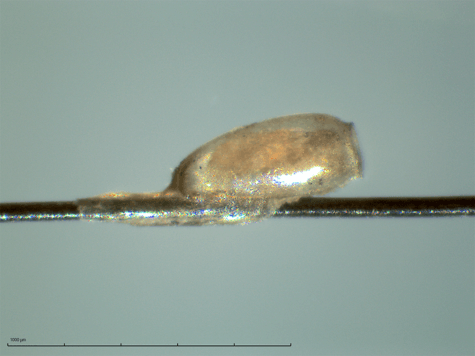

The team explains that head lice use this “cement” to essentially glue their eggs (nits) to the hair and scalp of people. Researchers found that even after 1,500 to 2,000 years, the nit cement kept the ancient humans' DNA in better condition than samples coming from other fossils — such as teeth and bone fragments. Their findings are providing new insights into the migration of pre-Columbian humans within South America.

“Like the fictional story of mosquitos encased in amber in the film Jurassic Park, carrying the DNA of the dinosaur host, we have shown that our genetic information can be preserved by the sticky substance produced by headlice on our hair. In addition to genetics, lice biology can provide valuable clues about how people lived and died thousands of years ago,” says Dr. Alejandra Perotti, an associate professor of invertebrate biology at the University of Reading, in a release.

“Demand for DNA samples from ancient human remains has grown in recent years as we seek to understand migration and diversity in ancient human populations. Headlice have accompanied humans throughout their entire existence, so this new method could open the door to a goldmine of information about our ancestors, while preserving unique specimens.”

Better samples in lice cement than bones

Typically, scientists extract DNA from ancient humans from dense bone fragments of the skull or inside teeth. Until now, they have provided the best quality DNA samples for research.

Unfortunately, these samples are not always available or ethical and cultural beliefs prevent scientists from damaging these remains. The new method of collecting DNA from underneath the nit cement may allow researchers to avoid these issues. Nits are a common thing scientists find in the hair and clothes of well-preserved mummies.

(CREDIT: University of Reading)

In this case, researchers collected DNA from nit cement from three mummified bodies from Argentina. These people reached the Andes mountains in Central West Argentina between 1,500 and 2,000 years ago. Study authors found even more nits on a textile from Chile and a shrunken head from the ancient Jivaroan people of Amazonian Ecuador.

The team found that these DNA samples carry the same concentration of DNA as a human tooth and twice as much as ancient bone fragments.

“The high amount of DNA yield from these nit cements really came as a surprise to us and it was striking to me that such small amounts could still give us all this information about who these people were, and how the lice related to other lice species but also giving us hints to possible viral diseases,” says Dr. Mikkel Winther Pedersen from the GLOBE institute at the University of Copenhagen.

“There is a hunt out for alternative sources of ancient human DNA and nit cement might be one of those alternatives. I believe that future studies are needed before we really unravel this potential.”

The nits died in the cold mountain trek

A review of the DNA revealed the first ever link between the mummies and humans in Amazonia 2,000 years ago. It's the first time researchers have found evidence that humans in the San Juan province migrated from the Amazon rainforest, in modern-day Venezuela and Colombia.

The team also found evidence of the Merkel cell Polymavirus in the DNA. This virus, officially discovered in 2008, is shed by healthy human skin. On rare occasions, the virus gets into the body and may cause skin cancer. These new findings point to the possibility that head lice may also help spread this virus.

As for the nits themselves, the team says it's likely these eggs died in the extremely cold temperatures in the Andes. Researchers found small gaps between the nits and the mummies' scalps along the hair follicles. Usually, lice glue their eggs closer to the scalp to keep them warm.

The findings are published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.